I’m always on the lookout for the genteel norms of an earlier life; forgotten values that are now in decay. It’s all about reporting on history, not glamorizing it.

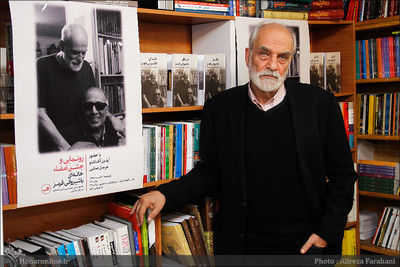

That’s according to Aydin Aghdashloo, an appreciated painter, graphist, writer, film critic, and artist in modern and contemporary art. This is the second part of his thought-provoking interview with us:

Your work, it’s all about individualism. Why so much emphasis?

That’s just part of a bigger picture. The first painting I ever liked was Individualism by Italian Renaissance artist Sandro Botticelli. His work has been seen to represent the linear grace of Early Renaissance painting. It’s the portrait of a faceless young man that’s been replaced by nature. As you see, conscience and subconscious have made my works somehow multi-layered. Part of it is subliminal, in which I live in the 1960s. This is a period when individualism was so important to the Iranian elite. They used to look for it in calligraphy paintings and Saqakhaneh (public drinking place), as well as classical art in movies and plays directed by Bahram Beyzaei and Hooshang Golshiri. This is a time when we witnessed various elements of individualism and perhaps it also had a profound impact on me.

As for the cognizant part, individualism means something else. The question of who am I and what am I. This is a question that Philosopher Omar Khayyam also raised centuries ago. When this question is raised, individualism becomes problematic. It goes well beyond the question itself.

I had to ask the same question from myself and that’s what made my works multifaceted. Just like other artists, one of my biggest tasks has to be to raise questions. That says why in the books and illustrations that narrate Khayyam, we see an old man holding a glass of wine and kneeling down before a beautiful woman. It’s all a misunderstanding. It’s not what it seems. What Khayyam does is raise questions and that’s all. In all, he keeps probing and questioning; who am I and what is individualism?

Tell us about your mindset in different periods and how it affected your work.

If you quest you will find. An individual whose work shows the thought of gradual death and doom should also say what exactly he means; the destruction of what? Gradual death and doom is a precious thing. It’s a disaster. Obliteration of anything is a disaster. But there is a big difference between tearing up a white paper and a miniature artwork painted by Reza Abbasi. The latter is an irreplaceable disaster. On the other hand, you can always replace a white paper. Here, the quest is for values that have been wrecked and gone. These values could mean a lot to any real seeker. If he likes the history of art, he will look for it and ultimately find its instances, its illustrations somewhere there.

These instances have to be portrayed and expressed though. True, any beauty meets its gradual death and doom, but is that a beauty in itself? An extraordinary individual will always choose from places that that are in line with his own inner self, related to his own knowledge and expertise. These are all instances (illustrations) of the quest, any quest. They could be straight, simple or complex. But they all illustrate an ideology, a world view.

Praising history, where does that come from? You teach history, you write history, and you create works with a historical touch.

It’s all a humble report on history. You cannot praise history all the time and from all angles. Reporting on history is different from praising it. When you praise history with eyes wide shut, you are under some kind of illusion. You cannot praise history with illusion. I only give a report on history. I go back in history and use it in any given work. But it’s not that far. Anything that has been built or ruined is an instance, an illustration for me.

I once painted the Malek Garden in Golab Darreh from different angles. The place was secluded but still splendid. Everything had fallen into pieces. If you wanted to report on it, it could have been something like this: A magnificent architecture from a by-gone era that has now turned into ruins, into naught. No more beautiful tile works on the walls, broken stone pool and tank instead, with a collapsed roof. But the trees are still standing there. Nature has found its way…

At least, that’s how I felt at the time. But when I went back to the same place later, the new owners had cut off the trees and constructed a tall residential building in place. I was downright wrong. It was money and greed that had found its way. I couldn’t tell the trees we all taste death and doom.

In all these instances though, things have come and gone. I also go back and forth in time. I don’t like what I see in Tehran over the past 50 years. There’s nothing interesting to report on. There could be few things to report still, but they are all on the brink of death and destruction one way or another; such as old mansions, old doors, old gardens. I cannot blend in and I cannot connect with the city. I like it, but I cannot blend in, I cannot admire the view. When I walk down the street I can see vividly how public taste has gone awry. It’s no longer captivating.

How do you assess your work throughout the years?

As a painter, it’s not my job to assess my works. It should never be this way. A painter does not need to know or teach the history of painting. I once accepted a job offer to complete two art projects. It lasted two years and disturbed me a lot. I still hate it when I remember. I was in charge of building two art museums. That was 30 years ago. I look back and I rebuke myself for accepting that silly job offer. I’m a painter and I should only paint. It was a foolish thing to do. I drew ten paintings at the time which was naught. Some might say it was worth my while. But I don’t think so. I wasted previous time. I should have only concentrated on the canvas.

I have given over 300 lectures in the same period. I have also written 12 books. I have had 5,000 students, yet drew only 400 paintings. I made a huge mistake somewhere. I should have only done painting; it is here that I could be remembered and fulfilled.

I gave few lectures before the 1979 revolution. You cannot compare the sheer volume and quality of my post-revolution works with those prior to it. I invested a lot of time and effort to prove myself. You cannot prove it to anyone else but yourself. I might have also tried to pay my dues to society. But that was a secondary concern. In truth, I worked hard to let the destructive world around me realize it can destroy neither me nor my individualism. The world cannot destroy an individual unless he destroys himself. I also tried to prove to myself and others that yes ‘I Also Am.’ I have different aspects to my character and personality, and I always have the answer to any question. Who knows? Perhaps, one day when I’m gone, all those answers would somehow reveal themselves in my paintings as well.

Translation by Bobby Naderi